Inside the .NET Garbage Collector — A Step-by-Step Journey Through Generational GC

Explained from scratch to deeper

For content overview videos

https://www.youtube.com/@DotNetFullstackDev

Modern .NET uses one of the world’s most advanced memory-management engines — the Generational Garbage Collector.

But despite how powerful it is, many developers still feel unsure about:

What exactly happens inside the GC?

Why does .NET divide memory into Generations?

How does the GC decide when to run?

What does “promotion to Gen1/Gen2” really mean?

When does Full GC happen?

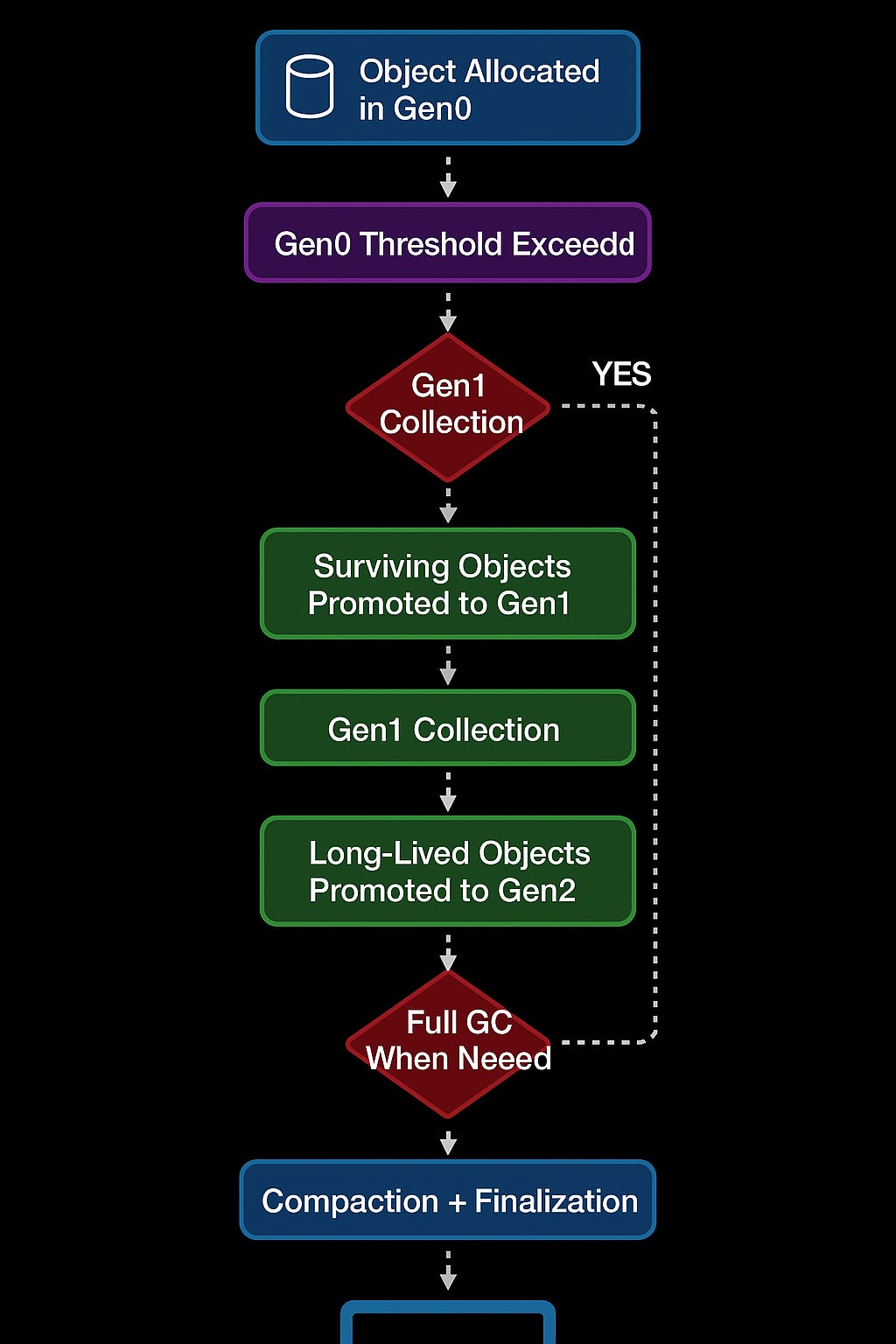

The best way to understand this is to visualize the GC as a flow, not a single event.

Below, we walk through each step of the Generational GC process.

🧩 Step 1 — Object Allocated in Gen0

“Every new object starts its life in the nursery.”

When your application executes:

var customer = new Customer();

.NET allocates memory for this new object in the Gen0 heap, which is designed for:

fast memory allocation

short-lived objects

minimal overhead

Think of Gen0 as a nursery — a space created for newborn objects.

Most objects in typical applications die young. For example:

temporary strings

LINQ intermediate objects

short-lived DTOs

loop variables

objects used inside methods only once

Because these objects are created and destroyed quickly, Gen0 is optimized to handle them efficiently.

🧩 Step 2 — Gen0 Threshold Exceeded

“The nursery fills up.”

Gen0 has a small memory size because:

small memory = fast cleanup

frequent collection = efficient space recovery

As your program runs, more and more objects are created:

new X()

new Y()

new Z()

Once Gen0 becomes full, .NET must take action.

This is when the runtime says:

“Gen0 is full — time to clean up!”

This triggers the next step.

🧩 Step 3 — Gen0 Collection

“The GC quickly removes objects that are no longer needed.”

A Gen0 GC is the fastest type of garbage collection.

How does GC know what to delete?

It pauses the application very briefly

Checks which objects are still reachable (alive)

Removes the ones that are no longer needed

All objects that survive this step get promoted to Gen1.

Why?

Because if an object survived a cleanup, it may be longer-lived.

🧩 Step 4 — Surviving Objects Promoted to Gen1

“If you survived the nursery cleanup, you move to the next room.”

Objects that weren’t cleaned up in Gen0 are considered more likely to live longer.

So .NET moves them to Gen1, which is a middle ground:

bigger space

collects less often

handles objects with moderate lifetimes

Typical Gen1 survivors include:

objects reused across multiple method calls

service instances

collections that grow during processing

cached objects

Think of Gen1 as a teenager stage — not newborn, not adult yet.

🧩 Step 5 — Gen1 Collection

“If Gen1 starts filling up, GC cleans it too.”

Eventually, Gen1 also fills.

When that happens, .NET triggers a Gen1 collection, which:

cleans up dead Gen1 objects

promotes surviving objects to Gen2

A Gen1 collection is slightly slower than Gen0, but still efficient.

This step only happens when needed — i.e., when Gen1 runs low on memory.

🧩 Step 6 — Long-Lived Objects Promoted to Gen2

“Any object that survives long enough becomes a long-term resident.”

Objects that survive Gen0 and Gen1 collections graduate to Gen2, the adult generation.

Gen2 contains:

application-wide services

large internal object graphs

caches

static data

objects that stay alive for the lifetime of the app

Gen2 collection is rare and expensive, so .NET avoids touching it frequently.

Think of Gen2 as long-term storage.

🧩 Step 7 — Full GC (Triggered Only When Needed)

“When memory pressure becomes high, GC cleans everything.”

A Full GC is the most expensive type of garbage collection.

It includes:

Gen0 cleanup

Gen1 cleanup

Gen2 cleanup

LOH (Large Object Heap) cleanup

Full GC happens only under conditions like:

very high memory usage

large object allocations

low available physical memory

explicit calls like

GC.Collect()(not recommended)

Full GC introduces a longer pause because the GC checks the entire managed heap.

.NET tries hard to avoid this, which is why generations exist — to optimize GC and minimize full collections.

🧩 Step 8 — Compaction & Finalization

“GC organizes memory and finalizes special objects.”

After deleting unused objects, .NET may:

1. Compact memory

This reduces fragmentation by:

shifting objects together

freeing large continuous memory blocks

Compaction is vital because memory fragmentation can crash your app or slow down JIT allocations.

2. Run finalizers (if any)

Objects with destructors (~MyClass()) are queued for special cleanup.

Finalizers delay collection, so avoid them unless necessary.

🧩 Step 9 — Execution Resumes

“The app continues running normally.”

Once GC completes its work:

memory is clean

generations are reorganized

objects are promoted or removed

memory pressure reduced

The application resumes exactly where it paused.

Modern .NET uses Background GC, meaning much of the GC work happens concurrently without stopping your program.

This gives you:

faster apps

smoother performance

less noticeable GC pauses

Keep the Momentum Going — Support the Journey

If this post helped you level up or added value to your day, feel free to fuel the next one — Buy Me a Coffee powers deeper breakdowns, real-world examples, and crisp technical storytelling.

⭐ Putting It All Together

The Generational GC system follows a beautiful, logical flow:

New objects go to Gen0

Gen0 fills → Collection happens

Survivors move to Gen1

Gen1 fills → Collection happens

Survivors move to Gen2

Gen2 grows slowly → Full GC if needed

Memory compacted & finalized

Execution resumes with fresh memory

This is not just cleanup — it is a performance strategy:

Fast cleaning of short-lived objects

Rare cleaning of long-lived objects

Reduced pauses

Smarter memory use

Predictable performance

This is why .NET’s GC is one of the best in the industry.